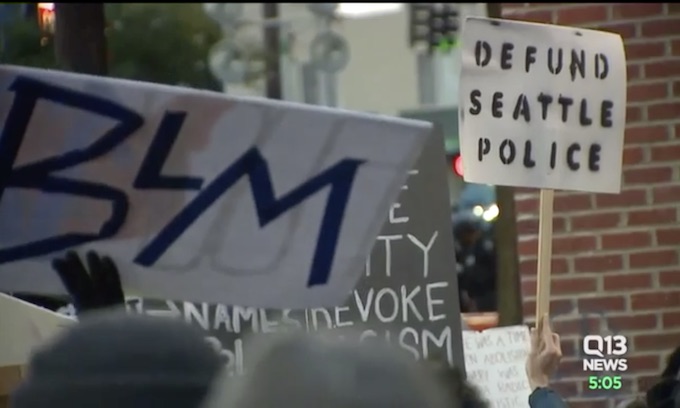

Hundreds of people again came together on Capitol Hill Tuesday night to protest police killings of Black people, gathering by Seattle Police Department’s newly boarded-up, vacated East Precinct and nearby at Cal Anderson Park. This time, there were no officers in sight.

“I’m glad,” said Rodney Maine, who wore a tank top that revealed a two-day-old Black Lives Matter tattoo and said his children regularly deal with racism at school. “It’s the best thing for society … They’re not helping.”

The precinct was festooned with banners and the surrounding area had the looks of a temporary encampment.

Also different Tuesday evening: Protesters flooded into City Hall after marching down from Capitol Hill, chanting that Mayor Jenny Durkan “has to go.”

Kshama Sawant (Genna Martin/seattlepi.com via AP)

Sawant raised a range of familiar themes, including demands to “tax, tax, tax Amazon.”

But Moe’Neyah Dene Holland, a protester who followed her, also drew applause when she responded, “I want to tax Amazon too, but can we please for once focus on Black lives?”

The marchers left City Hall around 10:15 p.m. and proceeded back toward the East Precinct.

When asked why she brought the group into City Hall, Sawant said it was essential that the power and uprising evident in the streets be seen in the halls of power in Seattle.

Demonstrations continued to yield political results Tuesday, as City Attorney Pete Holmes announced earlier in the day that Seattle would withdraw a legal challenge against King County’s revamped rules for inquests into police killings.

The rules would bar officers from testifying about their state of mind and would allow inquests to delve into their disciplinary histories. The city’s challenge, which has come under added scrutiny in the past week, opposed those changes and others.

In a statement, Holmes criticized the rules as vague, warning they would “leave much room for interpretation and inconsistency.” But he said he was bending to community demands heard “loud and clear.”

Meanwhile, a group of plaintiffs has filed a lawsuit in federal court against the city of Seattle, alleging the city has violated the constitutional rights of demonstrators against police brutality and racism by allowing police officers to deploy “unnecessary violence” in controlling and suppressing crowds. The plaintiffs include Black Lives Matter activists, protesters and a journalist.

The lawsuit alleges the city has deprived protesters and others of their First Amendment rights by using chemical agents such as tear gas and pepper spray, as well as projectiles such as flash-bang grenades and blast balls, to crack down on the free speech demonstrations sparked by the killings of George Floyd in Minneapolis and other Black people at the hands of police. The lawsuit also alleges the city has deprived protesters of their Fourth Amendment rights by subjecting them to excessive force.

Though Tuesday’s crowd-control lawsuit names the city as the defendant, rather than any individual, it repeatedly calls out Mayor Jenny Durkan and police Chief Carmen Best as responsible for authorizing the police actions. Rather than refute the allegations Tuesday, a Durkan spokeswoman described the lawsuit as “another step by the community to hold the city accountable.”

“On an almost nightly basis, the SPD has indiscriminately used excessive force against protesters, legal observers, journalists, and medical personnel,” the lawsuit says. “For example, SPD has repeatedly sprayed crowds of protesters with tear gas and other chemical irritants — including … just days after the city pledged a 30-day moratorium on the use of tear gas.”

The lawsuit also says: “With limited exceptions, these protesters have been overwhelmingly peaceful.”

Durkan and Best mostly stood by the Police Department’s actions last week, blaming problems on bad-actor provocateurs mixed in with nonviolent protesters and promising to have allegations of police misconduct thoroughly investigated.

The mayor and chief did apologize Sunday for instances in which they said officers may have failed to deescalate tense moments and used disproportionate force. Referring to police maneuvers on Capitol Hill, Durkan said, “I know that safety was shattered for many by the images, sound and gas more fitting of a war zone, and for that, I’m sorry.”

Hours after their remarks, tear gas was again deployed on Capitol Hill. Police said people in the crowd threw bottles, fireworks, rocks and other projectiles at officers. The next morning, multiple City Council members said Durkan should consider resigning.

In a dramatic shift in tactics Monday afternoon, the Police Department boarded up and barricaded its East Precinct and then abandoned the surrounding streetscape to protesters. The night passed peacefully.

“The mayor and Chief Best are committed to a thorough and complete review and report of the Seattle Police Department’s response to the protests and have already implemented a series of changes,” Durkan spokeswoman Kelsey Nyland said in an emailed statement.

The Police Department’s civilian-led Office of Inspector General and Office of Police Accountability are undertaking that review, which also will re-evaluate crowd management policies and training methods, with input from the Seattle’s Community Police Commission, Nyland said.

“The mayor and Chief Best have acknowledged that the city can and must do better for crowd management,” she added.

Nyland described the decision to withdraw from the East Precinct area Monday night as “an important step in the city’s efforts to lead with de-escalation and begin to rebuild community trust.”

Dubbing the intersection outside the East Precinct “Free Capitol Hill” and “Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone,” protesters took turns speaking Tuesday.

“Things are changing here,” organizer Sarah Tornai said. “It took so long. We fought so hard for this place. This is not a symbol, but a physical representation of police brutality.”

Sawant told protesters crowded onto the Cal Anderson Park playfield she would seek to reduce the Police Department’s budget by 50%.

Lawyers with the Seattle firm Perkins Coie, American Civil Liberties Union and Seattle University School of Law filed Tuesday’s lawsuit on behalf of Black Lives Matter Seattle-King County, four protesters, one would-be protester and a journalist with The Stranger newspaper.

The lawsuit asks for a temporary and permanent court order forbidding Seattle from continuing “using less-lethal weapons to control and suppress demonstrations,” along with a declaration that the city has committed constitutional violations.

Until recently, Black Lives Matter Seattle-King County urged would-be protesters to exercise caution, due to COVID-19 risks coupled with concern about police using chemical agents, the lawsuit says, alleging the city’s aggressive response has taken the group’s time and energy away from its core mission.

“These daily demonstrations are fueled by people from all over the city who demand that police stop using excessive force against Black people and … that Seattle dismantle its racist systems of oppression,” Livio De La Cruz, a board member with the local Black Lives Matter group, said in a statement.

“Rather than trying to silence these demonstrations, the city and SPD must address the protesters’ concerns by focusing on its policies and systems regarding police practices, use of force, and accountability.”

Seattle isn’t the first city to be sued for its response to recent demonstrations. A judge in Denver this week issued a temporary injunction limiting tear gas and other techniques. Edward Maguire, an Arizona State University expert on protest policing, said he expects to see a wave of lawsuits, with similar rulings.

The other plaintiffs in the Seattle lawsuit range from Abie Ekenezar, a veteran with disabilities subjected to chemical agents twice during the demonstrations, to Sharon Sakamoto, a retiree who says she was deterred from protesting because of health concerns over weapons like tear gas.

“During her time serving in the military, Ms. Ekenezar participated in tear-gas drills,” the lawsuit says. “She believes that the chemical agent the SPD used on her and other protesters on May 30 was tear gas. The tear gas stung Ms. Ekenezar’s eyes and triggered her asthma.”

Deeply committed to civil rights and racial justice because she survived incarceration as a child during World War II, Sakamoto, who is Japanese American, “was frightened away from joining the protests because of the SPD’s use of violence,” the lawsuit says.

The plaintiffs also include Muraco Kyashna-tochá, a protester who struggled to see after being exposed to police tear gas and pepper spray at a Capitol Hill demonstration she described as nonviolent. “Ms. Kyashna-tochá did not hear the officers issue any verbal warnings,” the lawsuit says.

The lawsuit blames Durkan and Best as the decision-makers at the city, saying “Mayor Durkan and Chief Best have acted with deliberate indifference to the constitutional rights of protesters and would-be protesters.”

Durkan and Best have continued to authorize unnecessary violence, despite mounting complaints and despite “acknowledging that the majority of protesters have been peaceful,” the lawsuit says.

The mayor’s office Tuesday sought to spread responsibility to other players. It was “under the previous (mayoral) administration” and with court supervision that the Police Department’s current crowd-management policies were developed, Nyland said, noting the City Council, City Attorney’s Office, “accountability partners” and U.S. Department of Justice all were involved.

“Not only do people have the right to peacefully protest, it is a historic and critical tool,” Nyland added. “Indeed, the mayor has protested and marched many times in the streets of Seattle and in the nation’s capital.”

Tuesday’s lawsuit says tear gas deployed downtown made protester Alexander Woldeab “feel like he was suffocating,” and says Seattle University School of Law student Alexandra Chen dealt with days of skin irritation after tear gas became trapped under the mask she was wearing to protect against COVID-19.

It says multiple journalists also have reported being “gassed or subjected to flash-bang devices by SPD,” mentioning a TV correspondent who was hit by a flash-bang grenade while recording live.

The lawsuit says Nathalie Graham, a journalist with The Stranger, had to stop covering demonstrations on May 30 and June 2 because she was having trouble seeing and breathing after tear gas and flash-bang grenades were deployed.

“There is a new element of trepidation, anxiety, and fear to my experience of being a journalist,” Graham is quoted as saying in the lawsuit.

Also Tuesday, the Office of Police Accountability added complaints about the Police Department’s most recent tear-gas deployment and the alleged use of flash-bangs to target a medic tent to a growing list of investigations related to the protests.

Seattle Times staff reporters Evan Bush, Percy Allen and Heidi Groover contributed to this story.

___

(c)2020 The Seattle Times

Visit The Seattle Times at www.seattletimes.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

—-

This content is published through a licensing agreement with Acquire Media using its NewsEdge technology.

Recent Comments