In a year marred by a deadly pandemic and rocked by civil unrest over policing in America, Chicago endured a level of violence in 2020 that reversed recent progress, with homicides increasing by more than 50%, according to official statistics.

Through Sunday, Chicago had recorded 762 homicides this year, a 55% jump over the same period in 2019, when 491 people in the city were slain, according to official Chicago police data. It is among the highest year-over-year increases in recent city history.

The total number of shootings this year also was up sharply. That figure rose by 53%, to 3,237 from 2,120, according to the police information.

City leaders and experts say the increase in violence likely was a byproduct of more than one factor. The spread of the coronavirus forced an economic shutdown and stay-at-home order, exacerbating economic woes in some neighborhoods and limiting some social services. The high-profile killings of Black people by police officers sparked a national reckoning on race issues, and in some cases generated instability across the city and increased distrust of police officers, eroding their ability to rely on community members for help.

Those who have long studied homicide rates say 2020 is also a clarion call to policymakers to reevaluate traditional attempts to reduce crime that rely heavily on police.

“What worries me is just how much has changed in the past year and how bad it (got) this past summer,” said Patrick Sharkey, a professor of sociology and public affairs at Princeton University, calling it a key time to find new strategies. “This is the moment. The trust in the old model has fallen substantially.”

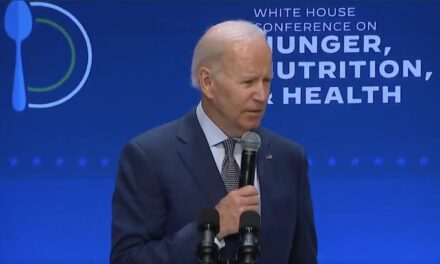

Asked this week about the increase in homicides, Mayor Lori Lightfoot acknowledged some communities have endured a particularly heavy loss of life from both crime and the coronavirus, exacerbating existing troubles.

“It’s been a hard time,” Lightfoot said. “Frustration, anger, unfortunately some of that is playing out in violence. A lot of things that are manifestations of trauma and mental health challenges have been in full bloom.”

The mayor’s hand-picked police superintendent, David Brown, said in a statement that violence reduction will take the cooperation of partners including the police, community organizations, faith leaders and others.

“The criminal justice ecosystem, however, was profoundly impacted and disrupted by the global coronavirus pandemic and the death of George Floyd,” Brown wrote of 2020, noting the violence problem was not unique to Chicago. “Our Chicago Police officers faced an unprecedented set of circumstances in contending with a spike in violent crime, made even more difficult by having to contend with a health pandemic while facing extended periods of heightened civil unrest and looting.”

From progress to dismay

Just a year ago, Chicago was in the midst of a third straight year of gun violence reductions.

New strategies and organizations had launched around the city, and there was an air of promise despite the remaining challenges.

Among the new initiatives was the West Side Sports Police & Youth Conference, which drew hundreds of children and offered competitive play at local parks in a variety of sports, including baseball and basketball.

Amaria Jones, a funny, giggly girl who loved to dance, was just one of the eager players.

But this year, Amaria, 13, became one of 55 young children and juveniles lost in the violence. Coach Brandon Wilkerson was left to help his players cope.

“Let’s give Amaria 12 seconds,” Wilkerson, 30, a lifelong Austin resident, would tell the players at the start of practices and games after Amaria was killed. The number 12 was her jersey number. “She’s in our minds. She’s in our hearts. Who (do) we do it for?”

They’d answer in unison: “Amaria Jones!”

A tough year from the start

The year began with higher than usual violence numbers, even ahead of the emergence of the coronavirus in February and March. And when the pandemic set in, it only added to a storm of conditions that led to the runaway violence.

The ensuing shutdown caused economic distress and piled on the trauma of loss, experts said, as the city’s most violent neighborhoods also saw loved ones die, at times disproportionately, from the virus.

Institutions like libraries, parks and schools that provide safe havens were shuttered. And some natural safety nets were gone too — blocks no longer filled with people out walking to the store or picking up kids from school.

“You take away the businesses, all the pieces of society that generally have eyes out, and you are left with young people, and a lot of young people, who don’t have resources or that level of support if they are left on their own,” said Chicago Police Department community policing Sgt. Jermaine Harris, who cofounded the sports league that Amaria played in and works with youth on the West Side.

The shootings and homicides continued to outpace last year’s totals throughout the summer in the wake of the killing in May of Floyd, a Black man, by a white Minneapolis police officer who knelt on his neck for nearly 9 minutes as horrified witnesses looked on. The killing triggered nationwide organizing and protesting against racism, especially in policing. In several cities, widespread looting also broke out, including in Chicago.

Instability set in, experts said.

The highly charged environment is likely to have caused some police officers, fearing their actions would be scrutinized, to stop aggressively policing. Many cops found themselves off their normal beats to address protest activity, while community distrust of police escalated.

Police across the country recognized their footing in their communities had changed. In a national survey this fall, police chiefs were asked what was the No. 1 thing they needed as they lead their departments. The top response was to restore the public trust.

“We were surprised,” said Chuck Wexler, executive director of the Police Executive Research Forum, which conducted the research. “The sense from police chiefs is this recognition something is broken in the relationship between police departments and communities, more so than ever today. Doing something about homicides means doing something about restoring public trust.”

Superintendent Brown agreed. He noted the department had shifted during 2020 to sending more resources into areas seeing the worst of the crime surge but said the key for police is a good relationship with the neighborhoods.

“The best way to reduce crime and violence is to prevent it from happening in the first place by building bridges and trust in the community,” he said in his statement.

The issues didn’t just bubble over in Chicago. Other large American cities saw 2020\u2032s issues manifest themselves in surges in violent crime.

Through Dec. 20, New York City, with more than three times Chicago’s population, saw slayings jump by 39% from the same time in 2019, to 437 from 314, official police statistics there show.

In Los Angeles, a city with more than a million more residents than Chicago’s 2.7 million, its 343 homicides in 2020 represented a 33.5% jump over last year, when 257 were recorded. That was according to LAPD statistics through Dec. 26.

Sociologists have noted Floyd’s death was a stark, painful reminder of decades of indignities and fear that people living in some neighborhoods have often suffered at the hands of police. This, they said, led to an increased potential for some to lash out.

“When you live under that precarity, there is the greater opportunity for any interaction with folks in your grouping to be heightened or more intense and more violent,” said David Stovall, a professor of Black studies and criminology, and law and justice at the University of Illinois at Chicago. “Your frustrations are expressed into people you are in proximity with.”

A young life lost

Amaria was among the victims caught in the summertime violence surge in Chicago.

A bullet fired from the street struck her inside her South Austin home over the Father’s Day weekend as she was showing her mother a dance move. Two teens, 16 and 15, who were standing on the porch also were injured.

Her teammates signed her #12 Austin basketball jersey for her family, writing sweet remembrances on it.

“Fly High, Yaya,” one message reads. And, up in one corner, next to the “n” in Austin, is a simple, “I love you.”

The jersey was presented to Amaria’s family at her funeral. Like many Chicago families, the Jones’ had already lost loved ones to gun violence by the time Amaria was killed — and after her death, her older brother, 18, was killed in December.

This is the kind of ongoing trauma her community was already facing, said Mercedes Jones, Amaria’s 27-year-old sister. So the year Amaria spent playing on a team and being with other kids was precious. She loved it all — the uniform, the team pictures, competing and helping everyone out in the league, her sister said.

“Growing up in the area we grew up in, sometimes kids battle with anger issues and resentment for what they see around them,” Jones said. “As soon as she got on that team … when she first got her uniform, she had the little shirt and shorts, she was so excited to just be a part of something.”

Harris, the Chicago police sergeant who cofounded the league, said he thinks it has succeeded because it was designed to have three anchor institutions — community organizations, police and clergy — running the programs. Each team, for example, aims to have a coach from each of the groups.

“With so many people around them, there were ways to stay in touch,” Harris said. “It was COVID-proof. You have to coordinate things so it happens at the same time to counteract the negative things.”

Wilkerson, the coach, recalled the call he’d get at exactly 3:05 p.m. each day from Amaria, who was looking for a ride to youth programs that Wilkerson runs when he is not coaching.

“Coach B, can you pick me up,” he said she’d ask each day, even though his answer was always the same.

“I said, ‘Yeah, Amaria you know we’re picking you up.’”

The impact on outreach

Chicago’s community-based violence reduction organizations, which rely heavily on jobs to help divert people from violence, faced challenges too.

Work was scarce during the pandemic. And as happened everywhere, communication went virtual, posing a special challenge for those in the field of outreach.

“You can say anything over the phone, but when I get to see you face-to-face, I can read your body language and tell what’s going on,” said Terrance Henderson, who works as an outreach supervisor for Chicago CRED, which stands for Create Real Economic Destiny, a community organization that assists people in the Roseland and West Pullman communities.

Meanwhile, Henderson suspected the unemployment benefits that flowed through some of the city’s neighborhoods might have had some unintended consequences.

“A lot of illegal guns was being bought. A lot of drugs were being sold,” Henderson said. “Then you had a lot of robberies that took place because now it’s more … people with money. It’s people that never had money with money.”

Outreach teams remained on the street, switching gears to deliver food to those in need and, in the early days of the pandemic, were some of the first workers to hand out sanitizer and educate people on how to protect themselves from the virus.

But the gun violence proved persistent — even though many feared it could have been worse without the new violence reduction infrastructure in the city.

“Without it, it would have been more chaos, more anarchy,” Henderson said. “We’d probably be over 1,000 homicides by now.”

Going forward

The historic jump in violence this year has left both academics like Stovall and those who work in violence reduction emphasizing how key the community voice will be going forward.

Henderson, the outreach supervisor, stressed his workers’ abilities to make inroads with people who don’t trust law enforcement.

“Right now, everyone fears the police. … If you have a conversation with someone, they’ll say, ‘The police have never helped me in my life. … They arrest me,’” he said. “The police don’t go into the areas where outreach goes.”

Over the past two years, Chicago has created its first Office of Violence Reduction, and in the most recent budget, dedicated $36 million to support community-driven strategies like Henderson’s work, which combines outreach and intervention with jobs, therapy and victim support.

The city is also piloting an alternative response program that would pair police with mental health professionals when answering certain 911 calls.

While these are all new efforts, many criticize the investments as not nearly enough to fully address the scope of the violence problem.

All of the tests for Lightfoot and Brown come as the coronavirus continues to wreak havoc in neighborhoods and on the economy, and pressure for policing changes here and across the country still is high. They also come as Brown’s department remains under a federal consent decree that mandates reforms, and as Lightfoot has struggled to control the fallout from a botched police raid that has renewed questions about transparency.

Those challenges are not expected to fade when the calendar turns to 2021.

___

(c)2020 the Chicago Tribune

Visit the Chicago Tribune at www.chicagotribune.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

—-

This content is published through a licensing agreement with Acquire Media using its NewsEdge technology.

Lori Lightfoot, a typical Democrat, who will not convict criminals of violent crimes. During the “peaceful protests”, no one was convicted for looting, burning buildings, assaulting and murdering people, burning cars and assaulting the police. Let’s keep criminals on the streets, right Lori Lightfoot? With criminals on the streets, according to the logic of the left, crime will go down. How did that logic work out for the left?

It doesn’t matter to Lightbrain and the rest of the Regressive Liberal Socialist Democrats… to them it’s that evil Constitution allowing citizens to have firearms… They will… NOT… listen to anything else…that’s all these pinheads know. If we just had socialism as a form of government then all the violence will vanish. If the general population lived in total abject poverty disarmed then the elitist ruling class can control it all. After all… it’s worked so well everywhere else in the world.

Commucrats, KEEP PROVING they are the party of lawlessness, and crooks.. SO of course their cities, they ruin, will have higher crime!

“The trust in the old model has fallen substantially.”,,,,,,,What?,,,,More like following the old model that worked has fallen PROGRESSIVELY and substantially by regressive secular socialist fools who have no concept of reality let alone what motivates the human condition to choose and follow paths of good and evil.

“a stark, painful reminder of decades of indignities and fear that people living in some neighborhoods have often suffered at the hands of police.”,,,,,portrayed by a manipulative socialist media of division that ignores the statistics that for every black killed by a cop, 100 are killed by a fellow black. Drugs and guns do not mix, and Democrat run cities of entitlement are the breeding grounds of the social destruction. Can’t think of one Republican run city with even a fraction of these problems.

IF we really were ‘following an old model’, we’d SWIFTLY be executing these criminal scumbags.. IN THE PUBLIC square.

Actually, blacks and guns don’t mix, and that is a proven fact. So what is the answer. It would be racist to take guns away from the 13 percent, so they try to disarm 100% to get the 13%. AND if you analyze the numbers further, you find that the male blacks representing less than 9% of the population, yet commit most of the violent crimes. Even then although the basic group, young blacks, are only 9% of the population, not all of them are criminals. So the progressives want to disarm and/or make 100% of the population criminals in complete and total disregard of the 2nd amendment, when the actual problem is mostly violent crime committed by well less than 9% of the population. Furthermore they are black but to point that out is racist?

SO true. Just look at the DECADES upon DECADES of violence in damn near ALL of africa..

The Democrat Party’s philosophy “Rule and Ruin”.

Note that the large cities with the most crime, murders, drugs and financial mismanagement are Democrat Party controlled.

And Note who these FOOLS vote for to mislead them. Nasty Nancy Pelosi, Maxine Waters, Adam Schiff, Chuck Schumer, Kamala Harris, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar, Ayanna Pressley and let’s not forget Tinkerbell PinoicollObama “Crooked Hillary” and “Beijing Biden”. etc. etc.

The democrap plan to reduce crime: Blame the police, elevate criminals to victim status, throw more money at “social” programs, teach minorities to hate whites and America in general, attack the traditional family structure, let criminals go free.

That should do it.

And don’t forget, BADGER THE HELL out of the criminals ACTUAL victims…

“The high-profile killings of Black people by police officers sparked a national reckoning on race issues….”

They mean: “The highly publicized and politicized death of criminals while resisting arrest sparked politically and financially motivated riots…”

It doesn’t cost any more to print the truth…. or facts for that matter.

This will be covered up by the Liberal Media and no one will know or care.

Ugly on a stick!

Lol haha haha

You put hatred for this country when ,you lie and say your ancestors were stolen not sold.So, yes they grow up with anger. Parents not marriage d ,father run off, so mama can get food stamps and welfare.

I was that little white boy bused to the hood.back in the 70’s same school, same teacher, same textbook. same classroom. I’m in my 60’s now and they still can’t pass. So that’s on them. I remember kids not showing up for school after spring break, like 80% not showing up for school. Not doing homework. I got up and went to the bus stop in the dark and got home in the dark. But I had to do my homework.

I’m still trying to figure out how that skinny, little, crackhead “queer” Lori Light-in-the-Loafers got elected Mayor of Chicago! Any ideas?

Richard Daley must be spinning in his grave. He was a Demoncrat and all, but still…

More “experts” – sociologists who get it wrong. Blacks commit more crimes (half of homicides at only 13% of the population) not because they’re policed by racists but because Dem Welfare programs addicted them and broke their family structure like all addictions. If anything, they’re under-policed because their communities are high crime areas. They’re already killing each other at 5000 or so a year and everywhere Black LIES Matter get police pushed back, the black on black death toll goes up. Black lives obviously DON’T matter to BLM who prioritize their delusion that blacks in America are hard done by when they are the most privileged blacks in the world as Candace Owens attests.

It’s not just Chicago, but all Democratic run cities. They are just not safe. Baltimore ,New York, etc. Not safe.