Like so many other changes to law enforcement, demands for civilian oversight of police often have their roots in outrage. Oakland’s first citizen review board came in the wake of protests over the 1979 police killing of a teenager named Melvin Black. In Los Angeles and San Jose, new accountability offices in the 1990s followed the videotaped beating of Rodney King

Now, more than two months into a nationwide movement against police brutality and racial injustice sparked by the police killing of George Floyd, the chorus is rising again for stronger civilian control of law enforcement agencies and officers, who critics say abuse their authority and answer to no one but themselves.

But what does “oversight” really mean? Decades after advocates identified civilian accountability panels as a check on police power, the landscape of those boards and commissions is patchy, uneven and, reform-minded critics charge, often ineffective.

“Civilian oversight is in the same category of most police reform” ideas, said Melanie Ochoa, a senior staff attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California. “Things look good on paper, but they require political will to actually make real — and I have yet to see that will.”

Fewer than 200 of the more than 12,000 local law enforcement agencies nationwide have some form of civilian commission or auditor. That means allegations of police abuses in most cities are typically investigated by a departments’ own internal affairs unit — a system many activists say lacks legitimacy. And any outside scrutiny of police is often left up to local governments that may be deferential to law enforcement.

Even among the oversight boards, members’ powers as watchdogs vary tremendously from city to city.

Oakland’s police commission is one of the most powerful in the country, with the authority to fire the police chief and sworn officers. But it still faces complaints from activists that it hasn’t meaningfully changed that troubled department’s culture.

Some commissions lack the legal authority or resources to investigate alleged misconduct, compel officers to testify or institute proposed reforms; even those with more teeth may see their calls for discipline ignored by police brass or watered down by arbitrators.

And many law enforcement leaders bristle at the idea of civilians calling the shots. Los Angeles County Sheriff Alex Villanueva in May defied a subpoena to appear before the county’s Civilian Oversight Commission, saying a measure voters approved earlier that spring to expand the commission’s legal authority was “unconstitutional.”

“I could not describe the perfect civilian oversight mechanism, because police unions and police departments and (elected officials) would find new and creative ways to subvert it,” Ochoa said. “There are just too many competing interests, and the biggest interests with the most power are the ones that are fundamentally against accountability.”

Oakland, San Jose and San Diego, among other cities, will ask voters in November to further expand their watchdogs’ powers. Dozens of smaller cities are also looking into creating oversight boards for the first time.

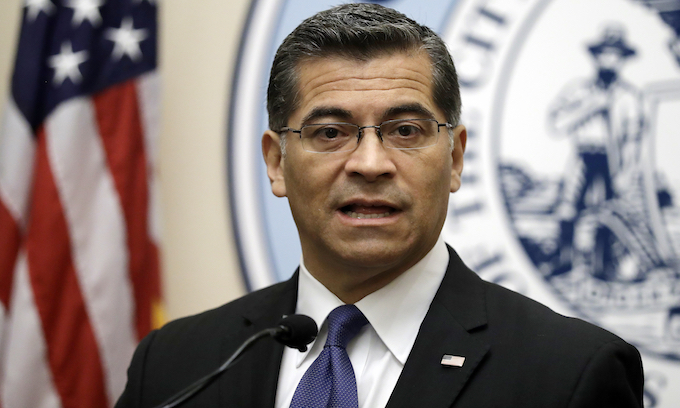

California Attorney General Xavier Becerra has taken a much more active role of working with troubled departments since federal authorities under the Trump administration backed away from the oversight role they have historically played. The state Department of Justice has launched investigations and reached reform agreements with police in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Bakersfield and other cities.

Days after a Vallejo police officer shot and killed an unarmed man named Sean Monterrosa this summer — the latest in a string of questionable police shootings in the small city in recent years — Becerra announced a new multiyear review and reform agreement to overhaul that department.

In an interview, Becerra said he views the DOJ’s role as a supplement for local police oversight that can step in to conduct broader investigations. Where local police commissions may have limited power, he said, the state constitution grants his department substantial authority to ensure those reforms are carried out.

“We can do them anywhere where we see a systemic violation of people’s rights by law enforcement agencies,” Becerra said of the reform agreements. “And we’ve used the tool successfully.”

Union resistance limits power

Each city with a police oversight office has had to navigate a raft of questions to figure out its approach: Should the office handle individual complaints of misconduct, take a bigger-picture view by scrutinizing policies and procedures, or do both? Should it conduct its own investigations, or let internal affairs units handle them? Should it have the power to impose discipline, or leave that up to the chief to decide?

As a result, those entities have had their missions and powers shaped by years of conflict between community activists pushing for tougher accountability measures and police — particularly rank-and-file officers’ unions — who have historically fought the creation of new oversight systems or sought to limit their authority.

With that pressure, a watchdog’s impact often depends on how aggressively its leaders wield their power — and whether local politicians back them up.

“You have to have strong political leadership that wants to lead the department, not follow the department,” said civil rights lawyer John Burris, whose lawsuits and investigations have helped spur many of Oakland’s police oversight efforts, including the massive “Riders” police abuse case that led to federal monitoring of the department for the past 17 years.

In Orange County, for instance, critics complained that the watchdog assigned to oversee the sheriff’s department — as well as other high profile public agencies — was instead far too cozy with the office, failing to hold it accountable even as the agency stumbled through a series of high-profile scandals.

“It has been a zero-impact office,” said Scott Sanders, the county’s Assistant Public Defender.

County officials fired the office’s leader in 2016 and at one point considered shutting down the Office of Independent Review. But a new director appointed this spring is raising hopes the office can get back on track, Sanders said.

In San Jose, officials ultimately “established the office but basically didn’t give it any teeth,” said retired Judge LaDoris Cordell, recalling the creation of the San Jose Independent Police Auditor’s office, which she led from 2010 to 2015.

Unlike police commissions and auditors in other cities, the San Jose auditor does not have the legal authority to investigate complaints or determine whether misconduct occurred — that work is still done by the San Jose Police Department’s Internal Affairs Unit.

“The police continue to investigate themselves,” Cordell said, “and that’s the biggest problem with the office.”

Tom Saggau, a spokesperson for police unions in San Jose, Los Angeles and San Francisco, disputed the idea that unions fight reform and oversight at every turn, noting that San Jose’s police union has endorsed the slate of changes that will go before voters this November to give the auditor’s office more investigative power. Then again, the union announced its support for those measures only after it mounted a successful campaign to push out an auditor it considered biased against police.

He and others in law enforcement charge that civilian boards are often too eager to bring the hammer down on officers. He insisted that the work of investigating officers should be left up to professionals who know how to conduct those inquiries.

“The current system of internal affairs is working as it should,” Saggau said. “I don’t buy into the premise that it is illegitimate.”

Activists skeptical too

Oakland’s police commission, which was revamped in a 2016 ballot measure, hasn’t hesitated to flex its muscles.

With the support of Mayor Libby Schaaf, the commission fired Chief Anne Kirkpatrick earlier this year after sparring with her over the pace of reform at the long-troubled department. Last year, it ordered the firing of five officers involved in the 2018 fatal police shooting of a homeless man. The commission has reworked the department’s policies for making traffic stops of people who are on probation and parole, and is now doing the same with its use of force policies.

“We were given (this) power by the citizens of Oakland and we are using it as we see fit,” said Regina Jackson, the commission’s chairwoman. “We are not afraid to make difficult decisions, but we make them thoughtfully and strategically.”

Kirkpatrick, police union officials and other critics have countered that the commission is an unelected board overstepping its power. At the same time, some activists say the commission hasn’t done enough.

Oakland’s Anti Police-Terror Project wants the commission to have even more authority and independence from city government, with members appointed from community organizations rather than the mayor or a selection panel.

“We’ve tried police commissions, we’ve tried boards,” APTP co-founder Cat Brooks said, noting that complaints about racial profiling, excessive force and questionable shootings have endured regardless. “We pay millions of dollars for oversight; it’s not happening, and it’s not working, because the reform that is needed is not tinkering around the edges.”

___

(c)2020 the San Jose Mercury News (San Jose, Calif.)

Visit the San Jose Mercury News (San Jose, Calif.) at www.mercurynews.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

—-

This content is published through a licensing agreement with Acquire Media using its NewsEdge technology.

“Who Watches-THE WATCHMAN.”?

Author xUnknown.