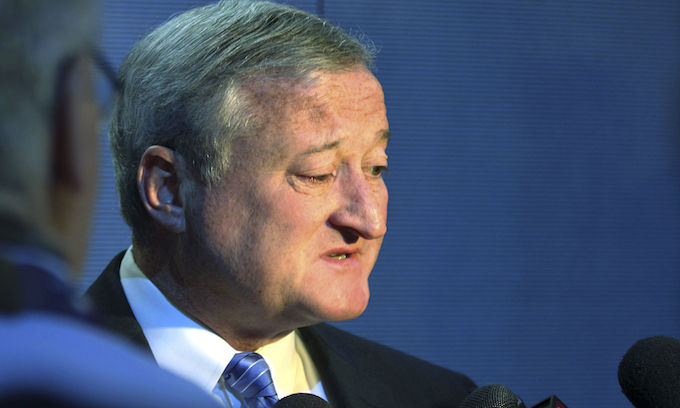

Mayor Jim Kenney’s $6.1 billion budget proposal unveiled last week includes streetlight improvements, free WiFi for families, and diverse police recruitment.

City officials say those items came from their “budgeting for racial equity” strategy launched in 2020 — months before the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis and the subsequent racial justice movement.

It’s too early to know whether Philadelphia’s approach will be effective in combating the city’s deeply entrenched racial disparities, with high poverty, gun violence, and metrics such as low voter turnout still concentrated in neighborhoods redlined in the 1930s. But policy experts describe a city taking steps in the right direction.

What is ‘budgeting for racial equity’?

In January 2020, Kenney signed an executive order that created a new diversity, equity, and inclusion officer and called on departments to detail employee demographics and establish strategies to hire people of color.

The order also launched the “budgeting for racial equity” initiative.

City departments are now required to develop racial equity frameworks for their offices. Department leaders work with the DEI office and an independent consultancy firm to identify their biggest barriers to racial equity and ways to address them.

The order created a Racial Equity Steering Committee, which includes 50 city department leaders and employees. The committee helps make recommendations that members feel could improve racial equity and that they want funded in the budget.

The racial equity budget report for the coming fiscal year is dense, with 226 pages largely made up of each city department’s responses to a series of questions about priorities, challenges, ongoing programs, and new opportunities.

Molefi K. Asante, a professor in Temple University’s department of Africology, said that he’s encouraged by the city’s progressive leaders but that tying equity to race can confuse people.

“The idea of ‘racial equity’ is difficult for me because what we’re really talking about is economic and social equity,” said Asante. “I think that ultimately if you talk about equity and race that people get the wrong idea.”

Has anything been funded for racial equity?

This year’s report identifies 30 programs that could potentially improve racial equity and were either fully or partially funded in Kenney’s proposed spending plan. The racial equity proposals prioritized public safety and antipoverty measures.

The resulting budget items include:

1. $3.7 million more for the existing right-to-counsel program, which provides free legal help for low-income tenants facing eviction.

2. An additional $300,000 for the city’s gun violence intervention program, which targets individuals most likely to shoot or be shot.

3. $2.9 million for staff salaries to allow the library system to remain open more consistently.

4. $700,000 for streetlight improvements and high-impact race equity priorities.

5. $700,000 for PHLConnectED, an ongoing initiative that offers low-income families with school-age children free WiFi.

What’s the point?

Impact, according to the city. Using metrics from the consultants, funding requests were measured by how much they’ll reduce the gap between Black Philadelphians or other people of color and white Philadelphians.

The city’s choice to publish some of the process is part of the impact, too, one expert said.

“I think that transparency is a critical step when starting a budgeting-for-equity process,” said a government budget consultant, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of their work with the city.

While most of the city’s 226-page report was just a Q&A with departments, the consultant said sharing raw data is the first step. “It starts to re-create trust, at least, that the effort behind this process is starting and it’s continuing.”

How does Philly compare with other cities?

After the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and widespread protests against police violence and systemic racism in 2020, Bloomberg Philanthropies launched its “City Budgeting for Equity and Recovery” program. Philadelphia joined the program, along with an initial cohort of 29 cities nationwide.

Philadelphia decided to prioritize safety and antipoverty initiatives this year, as the poorest big city in the nation, and as it faces historic levels of gun violence that disproportionately affect communities of color.

Racial equity priorities for other cities vary based on issues in different regions, the budgeting consultant said.

What do experts say?

“I do think that [city officials are] taking certain intentional steps to include the voices and the opinions of others within city government for the budgeting process outside of the finance office,” said the budget consultant.

Asante said he understands wanting to tackle poverty and gun violence but said the city should also invest in Black entrepreneurs to help close the wealth gap.

“The way these things develop sometimes gives the impression that African American people don’t have ideas or commercial projects, and they do,” said Asante. “We have a lot of ideas. But most frequently the problem is with being able to access the same sort of capital from bankers as other people.”

A city spokesperson said some racial equity measures that are in the budget proposal didn’t make it into this year’s initial report, including one from the Commerce Department aimed at diversifying contracts.

“I think that there’s something to say about, certainly, crime, about cleaning up the city, and about mitigating poverty,” said Asante, “but the best way to do that seems to me to encourage people with ideas to come and present those ideas and be funded. And let those people fly.”

___

(c)2023 The Philadelphia Inquirer

Visit The Philadelphia Inquirer at www.inquirer.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

—-

This content is published through a licensing agreement with Acquire Media using its NewsEdge technology.

It appears that Mayor Jim Kenney is suffering from rectal cranial inversion, should have that checked out by a doctor.

That seems to apply to EVERY Demon-rat mayor and guvnr.

Reckless, naïve, and racist view of crime and poverty. Criminals will continue to prey upon the community and spread mayhem beyond these communities. Thugs and low life scum do not care about these initiatives. They want less policing, less punishment, and more vulnerable residents to plunder.

Free wifi for low income families with children. Supposedly can’t afford wifi but they all run around with cellphones

And since most phone plans, HAVE Unlimited data, WHY DO THEY THEN NEED free wifi?

yes and that aint all they have deacon!