Portland officials say they expect less deployment of tear gas at nightly downtown demonstrations with the arrival of Oregon State Police troopers and the mayor apologized to nonviolent protesters gassed by city officers.

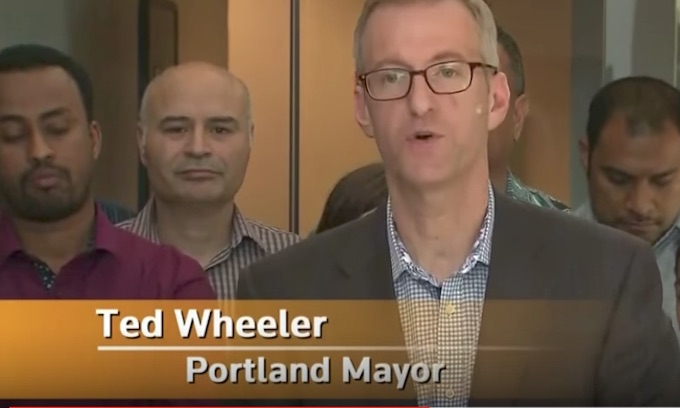

During separate news conferences Thursday, Mayor Ted Wheeler and Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty said all leaders were in agreement when they met with Gov. Kate Brown, State Police Superintendent Travis Hampton and Portland Police Chief Chuck Lovell on Tuesday “that Portlanders have been tear gassed enough.” Wheeler and Hardesty said Hampton agreed his troopers would use the toxic gas only as a last resort.

“The only reason to use tear gas when the federal government has left will be to save life, period,” Hardesty said. “No tear gas for crowd control. No tear gas because a water bottle got thrown at you and your feelings got hurt. The only reason that anybody will use tear gas will be to save someone’s life — either an officer or a community member.”

Wheeler and Portland police officials have said city officers have used the same criteria before electing to use tear gas during protests.

Gov. Kate Brown announced Wednesday a phased plan for federal officers to withdraw from Oregon’s largest city after at least two weeks of federal deployments ordered by President Donald Trump without the consent of local and state authorities. About 100 state troopers will be deployed to the city to guard the federal courthouse, which has been a flashpoint for about three weeks of the two months straight that protests for police reform and to end systemic racism have taken place.

Wheeler and Hardesty both expressed optimism that state troopers would help deescalate tensions, with Hardesty going as far to say she hoped city officers “learn a thing or two” from state police. Hampton told The Oregonian/OregonLive that troopers will wear their regular uniforms, not riot gear, during demonstrations.

Wheeler said he agreed with community members that Portland police officers’ use of tear gas “early on in these demonstrations” was indiscriminate and should never have happened. During a June 30 protest in North Portland, for example, Portland police used tear gas that hit people stuck in their homes or their cars as officers used the toxic fumes to force people away from the police union headquarters.

“I take personal responsibility for it and I’m sorry,” the mayor said of use of tear gas on unspecified occasions. Portland police used tear gas at the end of May and throughout June during demonstrations. Wheeler said local police used the gas only twice in July, when officers deemed a person or people faced risk of death or serious injury.

By contrast, he said that protesters have been indiscriminately tear gassed nightly for the past several weeks by federal officers. Federal officers used notably high levels of tear gas, impact munitions and other force on protesters Wednesday.

The city was sued in June and July over local officers’ use of tear gas and a federal court order issued in early June temporarily bars Portland police from using the gas unless officers believe someone’s life or safety is in danger.

Police Chief Chuck Lovell, who rose to that role on June 8, declined Thursday to directly address Wheeler’s assessment that officers misused tear gas, saying he wanted the city’s Independent Police Review to investigate community complaints. But he did not insist all uses had been appropriate.

“I suspect we’ll find instances where officers have violated policy,” Lovell said. “And we’ll deal with that through either discipline or corrective action.”

Before his news conference Thursday morning, Wheeler announced that local law enforcement and parks staff were kicking people out of Lownsdale Square, a city park across the street from the courthouse. He said it was part of the agreement with federal authorities.

Wheeler is the city’s police and parks commissioner.

Wheeler said getting tear gassed himself at a recent protest made him reflect on the irritant being hard to use in a targeted way and how it’s “not an effective tactic” because people return after it’s deployed.

“This is not going to be solved by public safety officers,” Wheeler said. “This is going to be solved by us committing that we have heard, understood and are demonstrably addressing the reforms and the changes that people have nonviolently been protesting for for weeks.”

Brown said agents with the U.S. Customs and Border Protection and Immigration and Homeland Security would begin leaving the city Thursday. But Acting Department of Homeland Security Secretary Chad Wolf didn’t specify when federal officers will leave entirely.

Wolf said a federal presence would remain in Portland until the Trump administration is convinced that state and local authorities can protect downtown federal property, including the Mark O. Hatfield federal courthouse. Wheeler noted that the U.S. Marshals officers who live in Oregon and normally provide security inside the courthouse will remain deployed there.

Wheeler said during the news conference he is “cautiously optimistic” that federal officers will leave and that he’s been working with the mayors of other major cities, including Seattle, to call on congressional leaders to pass new laws blocking the president from sending in federal authorities without consent from local officials. The Portland mayor admitted that the conflicting messaging coming from the state and federal government has been confusing, but said he sides with Brown.

“Ultimately, I trust the governor on this one,” Wheeler said. “I believe there is a deal and it’s my expectation, as well as the governor’s expectation, that that deal will be adhered to and the federal presence will leave.”

Wheeler and Hardesty said they weren’t concerned that the governor’s office negotiated with federal authorities on Portland’s behalf without direct involvement from city officials. They also said they didn’t foresee any complications working with State Police. Wheeler said state officers have coordinated with Portland police in the past while responding to demonstrations. One of those occasions was the protest on June 30.

Hardesty, who oversees the city’s fire, 911 and emergency preparedness responses, said she lifted her ban on Portland police staff using city fire stations as a base for tactical operations. She said state police could also use the stations, but the ban remains for federal authorities.

She said state police would act as the intermediary between Portland police and federal agents before they leave and that a state trooper will be embedded in the Portland police command center.

Wheeler said he views the departure of federal officers as key to revitalizing parts of downtown that have been hit hard by coronavirus-related business closures and borne the brunt of two months of demonstrations, including property damage. He said he hopes federal officers’ absence will deescalate violence at demonstrations.

Hardesty said she didn’t agree or condone violence being used during protests, but she said she understood why people do it.

“I cannot condemn people who are frustrated to the point where they’re busting windows,” she said. “I cannot condemn people who have been brutalized by federal forces and Portland police over the last two months when they throw water bottles at them. I can’t condemn them because I understand the frustration of continuing to try to seek justice and not getting it.”

— Everton Bailey Jr

___

(c)2020 The Oregonian (Portland, Ore.)

Visit The Oregonian (Portland, Ore.) at www.oregonian.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

—-

This content is published through a licensing agreement with Acquire Media using its NewsEdge technology.

Recent Comments