One of the nation’s strictest gun control measures will go before Oregon voters next month because of volunteer signature gatherers as young as 11 and as old as 94.

Measure 114 would require a permit to purchase a gun in the state and ban the sale or transfer of gun magazines that hold more than 10 rounds.

If approved, Oregon would join Washington, D.C., and 14 other states that have enacted similar permit-to-purchase gun laws. Nine states and Washington, D.C., have adopted laws banning large-capacity ammunition magazines.

While other gun permitting laws have faced legal challenges, courts have uniformly rejected them and found the laws constitutional. Multiple federal circuit courts also have upheld similar bans on large-capacity magazines, yet the nation’s high court recently directed the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals to revisit its finding upholding a ban in California.

Ballotpedia, a nonpartisan online political tracking website, has picked Oregon’s Measure 114 as one of 15 ballot measures across the country to watch on Election Day.

Backers of the measure, who include faith-based leaders, the Oregon Nurses Association, Ceasefire Oregon and Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, say the new permitting process is long overdue after similar efforts before state lawmakers died in committees. They are confident that the restrictions will prevent guns from getting into the wrong hands and help reduce homicides, suicides and gun trafficking.

“When our neighbors are bleeding, we cannot stand idly by,” said The Rev. Mark Knutson, one of the chief petitioners who leads Portland’s Augustana Lutheran Church. “We had an imperative to act.”

Opponents, including the Oregon Firearms Federation, the National Rifle Association and the Oregon Sportsmen’s Alliance, argue it’s too costly and would create a bureaucratic process that would be unwieldy and block prospective lawful gun owners.

Kevin Starrett, director of the firearms federation, argues the measure violates the Second Amendment. He said it’s “impossible to comply with,” and won’t have the desired impact.

Mass shooters would still be able to get their hands on the millions of large-capacity magazines now in circulation and not regulated elsewhere in the country, he argues.

“The measure will have no effect whatsoever on crime, no effect on the criminal behavior of the people who are not applying for the permits,” he said.

WHAT IT DOES

Under Measure 114, anyone who wants to buy a gun would have to obtain a permit, pay an anticipated fee of $65, complete an approved firearms safety course at their own expense, submit a photo ID, be fingerprinted and pass a criminal background check.

The background check would be more restrictive than one the state police currently conducts for gun buyers. An applicant could be denied a permit, for example, if the person “is reasonably likely to be a danger” to themselves or others, as a result of their mental or psychological state or “past pattern of behavior” involving violence or threats of violence. State police now restrict a gun buyer if the person was found guilty by reason of insanity in a criminal case, incompetent to stand trial and committed to a mental health institution.

A county sheriff’s office, which now processes concealed handgun licenses, would accept the permit applications and state police would conduct the background checks for the permits.

Applicants would have to complete law enforcement-approved firearms training. Courses could be taken at a community college, firearms training school, private or public organization or from law enforcement, the measure says. The course must include a review of laws governing ownership, purchase, transfer and use of firearms, safe storage, reporting of lost and stolen guns, and the impact of homicides and suicides on families. There also must be an in-person demonstration before a certified firearms instructor of an applicant’s ability to lock, load, unload, fire and store a gun.

A permit would last five years.

Licensed firearm dealers, private gun sellers and any sales or gun transfers that occur at gun shows would require validation that the buyer had a valid permit-to-purchase a firearm.

Once a permit holder wants to buy a gun, state police would conduct its usual firearms purchase background check, and that check would have to be completed before any gun were sold or transferred, under the measure.

This would close the so-called Charleston loophole. Under current federal law, firearms dealers can sell guns without a completed background check if the check takes longer than three business days. That’s how the gunman in the Charleston AMC Church mass shooting in 2015 bought his gun and killed nine people.

SUPPORTERS

Supporters of the measure point to studies by the John Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions, which found gun-related homicide rates dropped 28% over 22 years after Connecticut adopted a handgun purchaser licensing law in 1995. In Missouri, rates rose 47% from 2008 to 2016 after its handgun permit-to-purchase law was repealed in 2007, the center found.

The Rev. LeRoy Haynes, of Portland, and other proponents describe Oregon’s measure as a common-sense step that doesn’t “take guns away from people,” he said.

To him, the measure is personal. Portland tallied a record 92 homicides last year, and the city is on pace this year to reach or surpass that number.

Haynes said he has buried too many young men who have died from gun violence.

“This is a moral issue of saving our children,” he said.

Penny Okamoto, executive director of Ceasefire Oregon, said the new permits will help prevent suicides. “It puts time and space between someone who might be considering suicide and actually accessing that firearm,” she said.

McKay Moore Sohlberg, a professor at the University of Oregon who researches cognitive rehabilitation, lost her husband to suicide on April 25, 2011. Olof E. Sohlberg, a urologist and surgeon, had lunch with one of their three daughters and texted his wife about dinner. He then bought a gun at a local sporting goods store. Within two hours of the purchase, he was dead at home, she said.

“Measure 114 would have saved my husband’s life,” she said. “Our family lost our centerpiece.”

The Lift Every Voice Oregon campaign, the interfaith group that crafted the measure, launched shortly after the 2018 shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, where 17 students and staff were killed and 17 others injured. The group ran out of time to obtain sufficient signatures for similar petitions that year. Bills reflecting the initiatives never got a hearing in the state Legislature in 2019, and in 2020 and last year, the COVID-19 pandemic hampered signature-gathering efforts.

Recently, 51% of respondents in a poll of likely Oregon voters commissioned by The Oregonian/OregonLive said they would vote for Measure 114. As of mid-October, supporters had raised nearly $690,000 to promote Measure 114, more than nine times the roughly $71,600 raised by opponents, according to campaign finance records. Supporters of the measure have spent nearly $149,000 so far, with their largest expenditures going to consulting, research and placing statements in the voters’ pamphlet. Opponents have spent about $42,000 so far, with the majority of that money going to advertising.

“Never underestimate what can come from a church basement, a synagogue, a mosque or a temple,” said Knutson, once the initiative garnered enough signatures to make the November ballot.

CRITICS AND COST

Starrett and other gun-rights advocates argue that local sheriffs and police agencies, already stretched thin with staff shortages, wouldn’t be able to meet the need to process the permits, conduct the added background checks or provide the safety training.

The measure requires that a sheriff or local police department issue a permit to purchase a gun within 30 days after state police have completed a background check. But the firearms federation argues there’s no limit on how long the state police can take to do the check.

Both state police and local sheriff’s offices anticipate needing more staff to process the permit applications and conduct the additional background checks. State police will also need more staff to create and maintain a new database to track the number of annual permit applications, denials and reasons for denials.

The ballot measure, if it passes, is anticipated to cost both state and local governments $55 million in the first biennium, and about $50 million for each successive biennium, according to a state financial impact committee.

The anticipated revenue to local government from permit fees is projected at up to $19.5 million annually based on an estimated 300,000 applications per year.

State police estimate the agency would need to add 38 positions to handle the increased workload. In August, the state police reported it was working to reduce a backlog of firearm background checks due to an increase in gun sales from 2020. Each processor in the state police firearms unit can complete 10,782 background checks a year, according to the agency.

Opponents fear the measure will increase the backlog and cause unnecessary delays for people who lawfully can buy a gun, hindering their ability to obtain guns for their protection.

What others describe as a loophole — the federal law that allows a gun sale if a background check hasn’t been completed in three business days — Starrett calls a “safeguard,” for when the state police agency is unable to do its job.

George Pitts, chair of the Oregon Association of Shooting Ranges, called the measure “ludicrous.”

“We’re going to force all the law-abiding people to go through this circus, which will stop gun sales, but the criminals are not going to seek permits,” he said. “We’ll be making it harder for someone to buy a firearm to protect their family, which empowers the criminal.”

Opponents also say the required safety training is not readily available across the state. Jason Myers, executive director of the Oregon State Sheriff’s Association, said it will be nearly impossible to provide the training without significant state funding.

Bend Mayor Pro Tem Anthony Broadman said he wants state lawmakers to appropriately fund the measure if it passes. “We can’t put this on the shoulders of cities like mine to fund,” he said. “The state will have to step up. But it’s a small price to pay for something as important as this, which will impact public safety and public health.”

The Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions estimates that gun violence costs Oregonians more than $5.8 billion a year, said Anthony Johnson, spokesperson for the Measure 114 campaign.

Police can have private contractors provide the training, supporters counter. The measure doesn’t require live-fire training, but hands-on training that demonstrates the applicant knows how to fire a gun, through dry-fire training using an unloaded pistol, or mock or laser gun, he said.

Pitts, of the shooting range association, said training on a dummy gun won’t be effective, as each firearm is substantially different.

Oregon State Police would still have authority to fashion specific rules governing training, with oversight of lawmakers if the proposal becomes state law, Johnson said.

BAN ON LARGE-CAPACITY MAGAZINES

The ban on the manufacture, purchase, sale, possession or transfer of ammunition magazines capable of holding more than 10 rounds, excluding law enforcement and the military, is the most controversial provision. A violation would be a class A misdemeanor.

Proponents say it would reduce mass shooting deaths, as shooters would have to pause to reload before firing dozens of shots.

Michael Smith is chair of the Democratic Party of Oregon’s gun owners caucus and describes himself as a progressive gun owner. He said he can’t support Measure 114 because of its magazine-capacity ban.

The contention that a ban on large-capacity magazines would force a mass shooter to pause and reload overlooks the fact a shooter could simply carry multiple firearms or magazines, he said. He also believes that any evidence the ban would reduce shootings is inconclusive.

Members of the Oregon National Rifle Association, Oregon Firearms Federation and the Democratic Party of Oregon’s gun caucus contend it will bar the use of certain sporting shotguns meant for skeet and trap shooting, with built-in large magazines.

The measure’s drafters counter that it requires owners of such weapons to modify the magazines to hold fewer rounds. The measure also grants exceptions, allowing magazines that hold more than 10 rounds to be used for self-defense in a home, at shooting ranges or on private property for hunting, in compliance with state law.

But gun rights advocates counter that they’ll have to make an “affirmative defense” to show that they used or possessed a higher-capacity magazine in a lawful manner.

Further, they contend that the enforcement of the ban on magazines holding more than 10 rounds would disproportionately impact people of color.

The Oregon Criminal Justice Commission reported it was unable to predict the racial demographics of people arrested or convicted of violations should the measure pass.

Graham Parks, a Democratic Party state central committee member and Portland resident who opposes the measure, said Oregon could learn from Massachusetts’ experience, which has had a ban on magazines that hold more than 10 rounds since September 1994. Black people accounted for 29.5% of those arrested for having large-capacity magazines in Massachusetts, though they make up 12.4% of the state’s population, according to a 2020 report by Harvard Law School’s Criminal Justice Policy Program.

Miles Pendleton, president of the NAACP’s Eugene-Springfield region, said the victims of shootings are disproportionately people of color. A diverse coalition is behind Measure 114, he said. Pendleton said he found it odd that gun-rights advocates suggest police can’t be trusted to enforce the measure equitably yet are calling for more aggressive prosecutions of violent crimes that typically result in racial inequities.

Similar bans are in place in Washington and California. However, California’s ban is under court review. The U.S. Supreme Court in June told the 9th U.S Circuit Court of Appeals to revisit its case after the circuit court upheld the state’s ban following a suit filed by gun-rights advocates in federal court in San Diego.

Starrett said he’s convinced the ban won’t hold up in court.

Broadman, the mayor pro tem of Bend, was 12 when an assailant shot at his father while seated as a judge in California. He said he grew up with guns but supports Measure 114.

“If you need more than 10 rounds to protect your home or for sport shooting, I don’t know what to tell you,” he said. “But we’ve got a real public health problem. This seems like honestly a kind of no-brainer. Why wouldn’t we have reasonable training and prevent people from getting guns if they haven’t passed a background test.”

Smith, the chair of the Democratic Party of Oregon’s gun owners caucus, said he and other progressive gun owners are working on an alternative permit-to-purchase proposal that would designate the state Department of Motor Vehicles to handle the permitting process and not allow police to make what he believes are “arbitrary” decisions about applicants’ mental health qualifications.

Deschutes County District Attorney John Hummel and other supporters said they can’t wait. He said voters have a choice: “Are you for the status quo or are you for 114?…Because if you don’t have 114, you have the status quo. The status quo is unacceptable to me.’’

— Maxine Bernstein

©2022 Advance Local Media LLC. Visit oregonlive.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

—-

This content is published through a licensing agreement with Acquire Media using its NewsEdge technology.

the communist party of oregastan want you to be powerless to stop them just as all the demoncrats in this country.

go ahead and vote stupid.

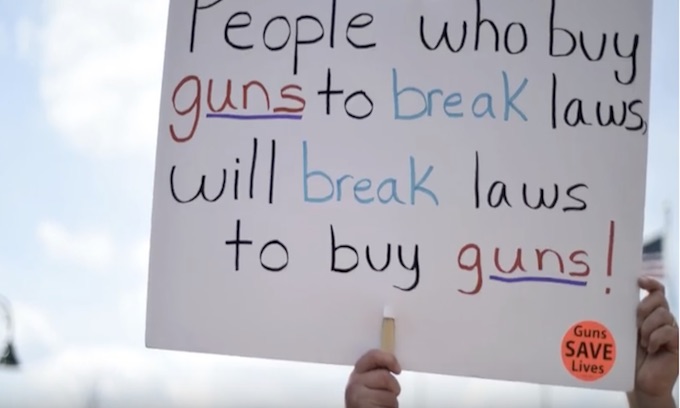

Exactly. HOW MANY LAWS Do violent criminals ALREADY IGNORE!?!?!?

And they think somehow, making just one more, will change that!

“The measure will have no effect whatsoever on crime, no effect on the criminal behavior of the people who are not applying for the permits,” he said.

This is just another attempt by the Democrat Party to have all guns registered with the Democrat Party’s socialist government in order for them to able to confiscate all guns if they desire.

#1. It is not the law abiding gun owners that indiscriminately shoot people.

* it is the drug dealers, the mentally unbalanced and Black men who kill the majority of people.

I.A.W. U.S. Census & FBI (Table 43a)

Black males make up about 7% of the U.S. population but every year commit ~56% of all the murders and ~64% of all robberies in the U.S… Every year in the U.S. there are ~6,000 African-Americans men, women and children killed and 92% of them were killed by fellow African-Americans.

When they come up with a way to keep guns from criminals, I might listen to their ranting. As usual, only law abiding people will be affected by the new laws. It should also be unconstitutional because people with limited means will be unable to comply with the new fees and costs for training. That’s blatant discrimination

That’s often something i raise TO LIBERALS, who kept whining about states pushing voter ID laws..

“IF Mandating someone get a photo ID issued by the state, even when SEVERAL STATES OFFER LOW INCOME FOLK TO Get their id for free, is Somehow Disenfranchising the poor, THEN HOW THE HELL IS mandating folks buy an EXPENSIVE PERMIT, Go through on their OWN DIME< classes to 'get qualified', and all these high tax levels for firearm/ammo purchases, NOT EQUALLY as Disenfranchising to the poor"??

YET NONE Ever seem to answer. Because they cant!

Good job you woke, LGBTQ, blm, antifa, voting sheeple for the Democrat party. You’ve helped destroy our country. Now, we conservatives will come in behind you and clean up your disgusting, low IQ selves.