The battle between Congress and President Trump over subpoenas for tax returns and testimony is far more complicated than it looks on TV. It’s not a slam dunk on either side of the court.

After special counsel Robert Mueller closed up shop with no charges against the president, the hopes of the bloodthirsty shifted to Capitol Hill, where Democrats hold the majority, the gavels and the subpoena power in the House of Representatives.

The chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, Rep. Richard Neal of Massachusetts, demanded that the Treasury Department turn over six years of Trump’s tax returns. A 1924 law allows a few lawmakers with oversight of the IRS to request the tax return of any taxpayer. Then again, sometimes the Supreme Court rules that laws are unconstitutional, even when they’ve been on the books for a long time.

Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin sent a letter to Neal saying the department needed more time to respond to the committee’s request. He wrote that he is consulting with the Justice Department “due to the serious constitutional questions raised by this request and the serious consequences that a resolution of those questions could have for taxpayer privacy.”

House Oversight and Reform Committee Chairman Elijah Cummings of Maryland subpoenaed years of the president’s financial records, drawing a lawsuit from Trump and his family business. The lawsuit contends Cummings has no “legitimate legislative purpose” for the demand and accuses Democrats of harassment.

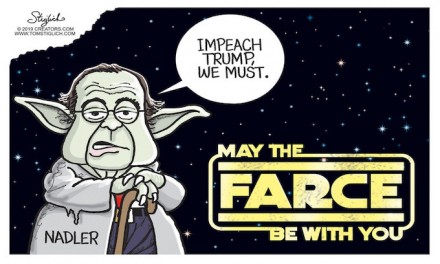

House Judiciary Committee Chairman Jerrold Nadler of New York subpoenaed former White House Counsel Don McGahn to provide documents and testimony related to the committee’s investigation of alleged obstruction of justice by the president.

“We’re fighting all the subpoenas,” Trump told reporters on the White House lawn as he prepared to head to Atlanta for a summit on the opioid crisis.

That statement is a tip-off that we’re watching a long-term negotiation.

While Trump may have an argument for privacy of personal and business documents going back years before he was president, anything involving employees of the government after he took office is in a different category. For example, Cummings has also subpoenaed the testimony of officials on matters related to security clearances and the upcoming Census.

Carl Kline, a former White House security director who now works in the Pentagon, was due on Capitol Hill for a deposition on Tuesday after one of his subordinates told the committee earlier this year that about two dozen people with “disqualifying issues” in their backgrounds were given security clearances anyway. The White House insisted on sending one of its lawyers to attend the deposition to ensure that executive privilege is protected; Cummings said no, and the White House ordered Kline to defy the subpoena.

Cummings also wants the testimony of John Gore, principal deputy attorney general for the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division, related to the decision to add a question about citizenship to the 2020 Census. The Trump administration insisted that a Justice Department attorney be allowed to accompany Gore to the deposition. Cummings refused. Gore didn’t go.

Cummings said the defiance of his subpoenas is a “massive, unprecedented and growing pattern of obstruction.” Trump said the Democrats are trying to use “nonsense” to defeat him in 2020 because none of their candidates can do it.

Is it a constitutional crisis? Not yet.

When Richard Nixon was president, the late Harvard law professor Raoul Berger, a constitutional scholar and legal historian, wrote some timely books with titles such as “Executive Privilege: A Constitutional Myth” and “Impeachment: The Constitutional Problems.”

These are deep dives into law and history. Berger reconstructs the debate at the time of the Constitutional Convention, explaining what was in the minds of the framers as they crafted the words that today are read by TV news hosts as the lead-in to a panel discussion on impeachment.

As is apparent from the title, “Executive Privilege: A Constitutional Myth” demonstrates that the Constitution created no such doctrine. The use of the term dates only to the Eisenhower administration.

To briefly summarize Berger’s comprehensive work: The Constitution gives Congress the power to impeach the president, the vice president and all civil officers of the United States. Implicit in the power to impeach is the power to investigate. There cannot be an unwritten constitutional privilege to impede the exercise of a plainly written constitutional power.

But it’s not quite that simple in practice. If the president refuses to produce witnesses or documents that have been subpoenaed by Congress, there’s not much Congress can do about it except file a lawsuit. Even a special prosecutor has no ability to force the president to cooperate with an investigation. All they can do is ask a judge to issue a court order.

If a president defies a court order, that’s a constitutional crisis, and that’s when you’d see an impeachment.

But there’s a risk for Congress and even for prosecutors in asking a court to overrule a claim of executive privilege: They might lose.

Because executive privilege isn’t really defined, its imaginary boundaries could be expanded as well as curtailed by a court ruling. For example, a court might create clear guidance on the president’s right to privacy of personal financial records, or on the confidentiality of legal advice or other consultations in the White House. A ruling like that would limit the ability of Congress to demand documents and testimony from future presidents.

It works the same way in reverse. If the president goes to court over executive privilege and loses, the power of future presidents in fights against Congress would be constrained.

So sometimes it’s in everyone’s interest to reach an agreement to cooperate, under specific rules and limitations, without a court battle.

Will that happen in the current stand-off? That’s the way to bet.

Susan Shelley is an editorial writer and columnist for the Southern California News Group. [email protected]. Twitter: @Susan_Shelley.

___

(c)2019 The Orange County Register (Santa Ana, Calif.)

Visit The Orange County Register (Santa Ana, Calif.) at www.ocregister.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

—-

This content is published through a licensing agreement with Acquire Media using its NewsEdge technology.

Recent Comments