Boeing said Wednesday that, due to the collapse in demand for airliners from the COVID-19 pandemic, it will cut widebody jet production rates in Everett and will study the feasibility of closing the 787 Dreamliner assembly line there to consolidate that work in South Carolina.

As the company announced a $2.4 billion loss for the quarter ending in June, Boeing said these moves will force further job losses beyond those previously announced, without specifying how deep the cuts will go.

In April, after the pandemic first locked down air travel, Boeing said it would cut “more than 15%” of jobs at its commercial jet business, principally in its Seattle-area operations, amounting to a 10% cut companywide in a combination of voluntary buyouts and layoffs.

Layoffs already announced will cut 10,500 jobs in Washington state. Wednesday’s announcement means further cuts are likely to be concentrated in Everett.

That’s because air travel demand is particularly low on long-haul international routes flown by the big widebody jets built in Everett, and this sector of the market will likely take much longer to return than domestic air travel.

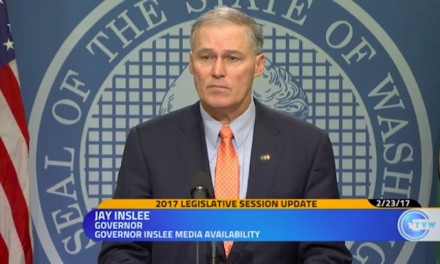

In a message to employees, Boeing CEO Dave Calhoun said customers “are delaying jet purchases, slowing deliveries, deferring elective maintenance, retiring older aircraft and reducing spend — all of which affects our business.”

He said Boeing will cut production of its large 777 and new 777X jets to just two jets per month in 2021, one less than previously announced.

And he said Boeing will delay the new 777X jet’s entry into service until 2022, rather than delivering it in the middle of next year as previously planned.

Earlier this month, Tim Clark, president of key 777X customer Emirates, told the Seattle Times that he didn’t want the plane until 2022 and suggested that program delays would likely lead Boeing to want to delay it anyway.

Calhoun also said Boeing will finally end production of its most famous jet, the 747 jumbo, in 2022. In the past month, the pandemic has forced airlines around the world to retire that aircraft early.

And most critically, Boeing will cut 787 Dreamliner production from 10 jets per month now to just six per month next year. Boeing had previously said it would go down to seven per month in 2022.

At that slow rate, Calhoun told employees, Boeing will now study “the feasibility of consolidating production in one location.” That one location can only be South Carolina.

The 787 is built on separate assembly lines in Everett and in North Charleston, S.C. However, the largest model, the 787-10, can only be built in the South Carolina plant, because its fuselage section is too large to fit into the Dreamlifter cargo transport plane that ferries parts to Everett.

So if there is to be just one site for 787 production, Everett will lose out.

The 787 is the Boeing widebody jet most likely to be in demand when international air travel does return. The prospect of losing it, combined with meager 747 and 777 rates, raises the specter of the largest building in the world by volume left largely empty of production. The plant currently employs more than 30,000 workers.

The 787 was launched in 2003 after Washington state provided massive tax breaks to convince Boeing to build it here. The state now faces the prospect of losing that work.

However, if Boeing does consolidate the work in South Carolina, there’ll be no impact on the company’s tax liability in Washington state because those tax incentives are already gone. In March, at Boeing’s request, the state legislature ended the aerospace tax breaks to comply with World Trade Organization rules barring subsidies.

Boeing’s Renton plant where it assembles the 737 MAX will not escape the impact of the pandemic slowdown. Calhoun said once the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) clears that jet to return to service in the U.S., expected sometime this fall, Boeing will ramp up production more slowly than previously planned.

The target now is to build 31 MAXs per month by early 2022. Earlier, Boeing had hoped to reach that rate next year.

Calhoun in the conference call with analysts cited the “geopolitical environment” as a factor in slowing the MAX ramp up. This appears to be a reference to the tensions between the U.S. and China. Chinese airlines are key customers for the MAX.

The $2.4 billion loss in the second quarter included more than $1.3 billion in write-downs for production slowdowns, severance payments and temporary closures because of virus outbreaks in Boeing factories. It compared with a loss of $2.94 billion in the same quarter last year, when Boeing took a $5.6 billion charge to cover compensation it owes airlines for the grounding of their MAX jets.

During a conference call with Wall Street analysts, Chief Financial Officer Greg Smith detailed the latest projections of the cost to Boeing of the 737 MAX crisis.

He said abnormal production charges due to the grounding of the jet is projected to reach $5 billion, of which $1.5 billion has already been incurred. And he said compensation to customers for late deliveries is projected to total $9.6 billion in cash or other forms of compensation. Of that amount, Boeing has already paid out $2.6 billion and has reached settlements with customers on a further $3 billion of the remainder.

The company reported a loss per share of $4.20. The average forecast of 20 analysts in a FactSet survey was a loss of $2.57 per share.

Revenue fell to $11.81 billion, down from $15.75 billion a year earlier. Analysts had expected $12.95 billion, according to FactSet.

In a note to investors, Rob Stallard, an analyst with Vertical Research, said all aspects of Boeing’s financial results were worse than expected.

“We would like to think that this is as bad as it gets for Boeing, but the … rate cuts that have been announced today put further downward pressure on expectations for the out year cashflows,” he wrote. “We continue to think that the plethora of downside risks are not fully reflected in Boeing’s current share price.”

After the market opened, Boeing shares fell about 2.5% in early trading.

Information on the financial results from The Associated Press is included in this report.

___

(c)2020 The Seattle Times

Visit The Seattle Times at www.seattletimes.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

—-

This content is published through a licensing agreement with Acquire Media using its NewsEdge technology.

Recent Comments